16 - Keys to successful collaborations, part 1: Negotiate authorship in advance

Clarify your field's publishing culture and agree on a publication roadmap

Reading time: 10 mins

In collaboration, any point you don't clarify will come back and bite you

A collaboration gone wrong can ruin your career (and your sanity). Yet the US Office of Research Integrity wrote:

“We are struck by how many disputes could have been avoided if only the collaborators had taken a few precautionary steps at the outset.”

Research on collaboration shows that unclarified assumptions are the #1 reason for disputes and sometimes major conflicts. Most assumptions end up being wrong, because collaborators often have different expertise and career needs, in addition to coming from different backgrounds, cultures, and institutions.

So, don’t assume anything – clarify your expectations and those of your collaborators. As the saying goes:

“You should never A.S.S.U.M.E. anything because it makes an ASS of U and ME.”

Pay special attention to authorship and data/samples format

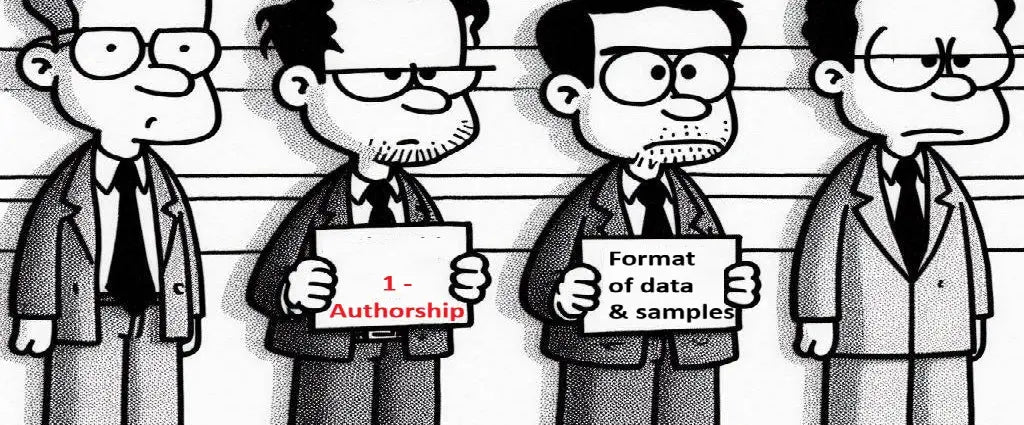

Fortunately, the two main disagreements in collaboration have been well identified: 1) authorship, and 2) the format of the data and samples shared among collaborators.

Therefore, in this post, we will learn how to negotiate authorship in advance. In the next post, we will learn how to agree on the format of shared data and samples.

The usual suspects of collaboration disputes

Authorship is Usual Suspect #1 in collaboration disputes. And that’s no wonder, as the stakes are very high. A publication can make a career, whereas not having one in time or in a suitable venue can break a career. To make things worse, rules for authorship vary between fields and are often quite nebulous.

Thus, you need to clarify the publication culture and needs of each prospective collaborator, and to agree on a publication strategy. Let’s get started.

1) Clarify the publication & authorship culture of each prospective collaborator

The publication culture comprises many elements, from the order of authors to publication venue, costs, and expected frequency of publication...

Consider the order of authors. In some subfields of physics, authors are listed alphabetically. In other fields, the order matters. In sociology, the first author may be the senior contributor, who provided intellectual guidance. In contrast, in biology, the first author corresponds to the junior contributor who carried out the main experiments. In some fields, being a corresponding author is significant; in others, it is inconsequential.

Then there are publication venues, costs, and frequency. In some fields, you must publish in open-access journals and budget additional money for that. In others, the main venue for publications is not a journal but symposium proceedings. Some fields expect annual publications, while in others publications are rare.

To complicate matters further, in fields like engineering, success might be measured in patents or working prototypes rather than publications.

I hope the above makes it clear that you cannot guess the habits for authorship in your collaborator’s field – instead, you must be curious and discuss them.

“I see the importance of understanding each collaborator’s publication culture. But how can we agree in advance on a publication strategy? Doesn't it depend on our results?”

Indeed, and you will never get the results you expect. But as a famous general said: “Plans always fail, but they are indispensable.” You should agree on a roadmap, not set arrangements in stone. It should anticipate various types of results and be open to renegotiation. I’ll provide an example at the end of this post.

Plans always fail, but they are indispensable

Now that we understand why authorship disputes arise, let's look at three widely accepted principles that can help clarify authorship expectations early on.

Three commonly agreed rules of thumb for authorship

I recommend discussing the principles below with prospective collaborators to see whether they agree, or have other principles to suggest – this will prevent most disputes down the line. As a bonus, this depth of discussion helps weed out freeloaders who’d want to be included as co-authors (it happens).

DISCLAIMER: These rules of thumb are not exhaustive and should be used as guidance to spark discussion.

A) Having contributed at least one figure or table qualifies you for authorship

It is commonly agreed that if you have generated data that is used for at least one figure or table in a paper, you should be included as a co-author.

Reciprocally, if a member of your collaborator’s team wants to invite themselves to a paper despite not having contributed data for a figure or table, you may ask your collaborator “Can you please tell me for which figure or table your team member has contributed data?”

I have used this question to prevent someone who had no role whatsoever in the paper, neither intellectual, technical or financial from inviting themselves as an author. I have also seen it successfully used by others.

B) You deserve a good author position if the paper wouldn’t be the same without you

Could anyone else have done your work, or did you provide a unique technical or intellectual contribution? This criterion helps assess your position in the author list where relevant. For instance, if you used a standard questionnaire to interview a few people, your position in the author list should be less prominent than if you developed an original approach to test a hypothesis and then designed the study protocol.

Of course, you should apply this criterion to yourself, not only to your collaborators: if you’ve done a standard experiment that most researchers could have done, whereas your co-author has done a delicate analysis that only they master, please do not claim first authorship.

C) An author should be able to present the paper’s results in context at congress

The important words here are ‘in context’. Have you ever seen a researcher present the work of a colleague or student when it was clear from their attitude and replies to questions that they didn’t understand much of the study? They have not had a meaningful scientific contribution to the study, and it is generally considered that they do not qualify to be a co-author.

“I don’t agree with this criterion. As a P.I., I provided the money for the study. It’s a lot of hard work – why wouldn’t I have authorship?

I get you; I have been there too. Finding money and providing the initial idea for a study is indeed very hard work, and being a co-author will help you stay motivated and obtain grants to support the team. But to qualify as an author, a P.I. should also provide scientific support to their team throughout the study. That is, when experiments don’t work and team members start going through a long slog, a P.I. should continue to guide them and provide ideas as well as moral support…

[Note: a solution to alleviate pressures on authorship may be to introduce a ‘Management contribution’ section in papers to recognize the funding and administrative efforts of senior researchers].

| Tip: If you cannot reach an agreement with prospective collaborators on who qualifies for authorship, don’t collaborate with them! |

Once you’ve understood the publication habits and needs of each collaborator, you need to agree on a publication plan for your collaboration.

2) Agree on a publication roadmap

| Tip: at the beginning of authorship negotiations, use the terms ‘junior’ and ‘senior’ author instead of ‘first’ or ‘last’ author. |

We'll use an example to illustrate the process of agreeing on a publication and authorship strategy. This example involves two teams. Team #1 is composed of a P.I. and a PhD student, and team #2 of a P.I. and a postdoc. Note how they come up with several scenarios depending on how experiments might work out.

Example of agreeing on a publication roadmap

P.I. #1: “I must publish within 2 years because my grant comes up for renewal and I need a publication as proof of concept. And my PhD student needs a junior or co-junior authorship”.

P.I. #2: “As for me, I need to publish as senior author in one of the leading journals of my field because that’s what my university requires for tenure. And my postdoc would need to be co-senior author in order to demonstrate independence for applying for a fellowship.”

P.I. #1: “Ok, so here’s what I propose – tell me if it’s fine by you:

1) If we can demonstrate that our hypothesis is right and subsequent experiments work, we can aim for journal A or B [leading journals of the field]. You’d be senior author and your postdoc co-senior author. My PhD student would be joint author and I’d be joint junior author.

2) If we can demonstrate that our hypothesis is right but subsequent experiments don’t work, we can aim for journal Z, with the same authorship arrangements; journal Z is not one of the leading journals of the field but presumably we’d stop the experiments after only a year, so you’d have time to work on other research topics after that.

3) If we can conclusively prove that our hypothesis is false, we’ll publish a short note in journal A, for example in its ‘Controversies’ collection, with the same authorship arrangement. It would be enough to demonstrate your postdoc’s independence to the tenure panel.

4) If we cannot determine within 6 months whether the hypothesis is true or false, then we call it a day and stop the collaboration.

This arrangement can be renegotiated if the results are too different from those anticipated, or if the collaborators don’t meet their duties. What do you think of this proposal?”

|

Tip: after all parties have amended and accepted it, email the final arrangement to all prospective collaborators and keep it in your records (no need to sign it with blood! :-) |

“Very interesting. But the arrangement only works because P.I. #1 is willing to be junior author; usually, both P.I.s want senior co-authorship.”

Indeed, the example is somewhat unusual because P.I. #1, not having strong career needs, was willing to take junior co-instead of senior co-authorship to accomodate the needs of postdoc #2 (it happens – I made a similar arrangement once). Now let’s see what happens if P.I. #1 had also wanted senior authorship.

Fulfilling all collaborators' publication needs might require a bit of creativity

In the above example, what if three collaborators had wanted senior authorship (e.g. P.I. #1, P.I.#2, and postdoc #2)? You’d need to get creative in order to satisfy all parties. You might propose to produce two papers:

1) A short technical note, with postdoc #2 as senior author. Indeed, to demonstrate their independence, any paper with senior authorship will do, even short.

2) A second paper containing the bulk of your results, in which P.I.#1 and #2 are joint co-senior authors.

“Waow, this arrangement truly does meet everybody’s needs.”

Indeed. On top of that, publishing the results of your collaboration as two papers rather than one will probably make the writing easier, since the complexity of a paper increases roughly as the square of the number of results it contains…

Common objections

“I’m afraid to negotiate authorship.”

You needn’t be afraid, because the vast majority of researchers will actually be reassured that you want to discuss authorship before engaging in collaboration. They too have authorship needs, and they know that the best time to negotiate an agreement is before a problem has occurred!

“I get it, but I’m afraid to negotiate anything really.”

You’re not alone – I hear this often in my courses. Yet negotiating is such an important skill that being afraid to negotiate will make both your work and life miserable. Therefore, I highly recommend that you take negotiation and assertiveness courses (ones that are geared towards researchers).

Such courses typically only occur a few times each year, so in the meantime, you can go to your local bookshop and look into the personal development section. Look for books on asserting yourselves, e.g. learning to say ‘no’, and on negotiation. I recommend a famous book, ‘Getting to Yes: Negotiating an agreement without giving in’, which is an easy but useful read.

If this helps, remember that collaborations make or break the career of young researchers and can damage even that of senior researchers...

NB: if you think your fear of negotiating may come from childhood trauma (which is frequently the case), I also recommend ‘The Myth of Normal: Illness, health & healing in a toxic culture'.

And that's it for Usual Suspect #1 in collaboration disputes: authorship. In the next post, we will learn about Usual Suspect #2: the format of data and samples...

Have a nice day and fruitful research. David

PS: If this post is useful, consider linking it to your website, and let me know at david_at_moretime4research.com. Thanks.